The Future of Creativity?

- Art/

- Creativity/

- Culture/

- Social Destinations/

By Davina Lee and Marc & Chantal

Share

An Extremely Large Drawing in West Kowloon, Hong Kong, by Sara Wong + 元新 Groundwork brought conceptual art to a broad demographic in a public space.

Hong Kong has seen a fundamental change in the cultural landscape over the last ten years. In the light of these changes what does the future hold for creativity in Hong Kong?

Most discussions of art in Hong Kong draw back to the description “cultural desert” a term so overused that no one can really be sure how or by whom the term was coined. Whatever its origins, the perception of Hong Kong as a place lacking in culture has existed alongside the inherent creativity of the city, including Hong Kong’s genius for improvisation, shan zhai innovations tailored to local market desires, and the creation of a unique Hong Kong culture combining Chinese culture with elements borrowed or adapted from Western culture, such as the ubiquitous cha chaan teng and the blurring of the boundaries between art and design and art and commerce.

Art (R) Evolution

In recent years, there has been unprecedented interest in and support for art and creativity from many quarters. The Hong Kong Government, attempting to rationalize and measure the creativity of Hong Kong society, produced two unrelated research projects that were conducted separately and published around the same time. In 2005, the Home Affairs Bureau (“HAB”) produced a so-called “creativity index”[1], which overlapped with a study published around the same time by the Hong Kong Arts Development Council (“HKADC”), established as a statutory body in 1995 to support the broad development of the arts, on “Hong Kong Arts and Cultural Indicators”.[2]

Both studies recognised the importance of “creative capital” of different types, including “structural/institutional, human, social, cultural and creative”[3] and the “creative economy”. Investing in Hong Kong’s future as a major art capital, the HK$21.6 billion West Kowloon Cultural District is slated to open in 2017, bestowing upon the city a world-class cluster of art museums and performing arts venues.

Bypassed for many years by the international art world in favour of Beijing and Shanghai, major players in the art world have woken up to the city’s position as the third biggest auction market after London and New York and home to the new Asian edition of Art Basel. The city has seen an influx of international galleries such as White Cube and Gagosian with their stellar rosters of artists, which are broadening Hong Kong’s existing infrastructure of home-grown galleries and alternative art spaces such as Para/Site, 1a Space and the Asia Art Archive. Occupying a unique position is Swire Properties’ Artistree, a 20,000 square foot multi-purpose space which has made its mark on Hong Kong’s cultural landscape with innovative exhibitions, music programmes and other events.

Cultural Change - The Art of Shopping

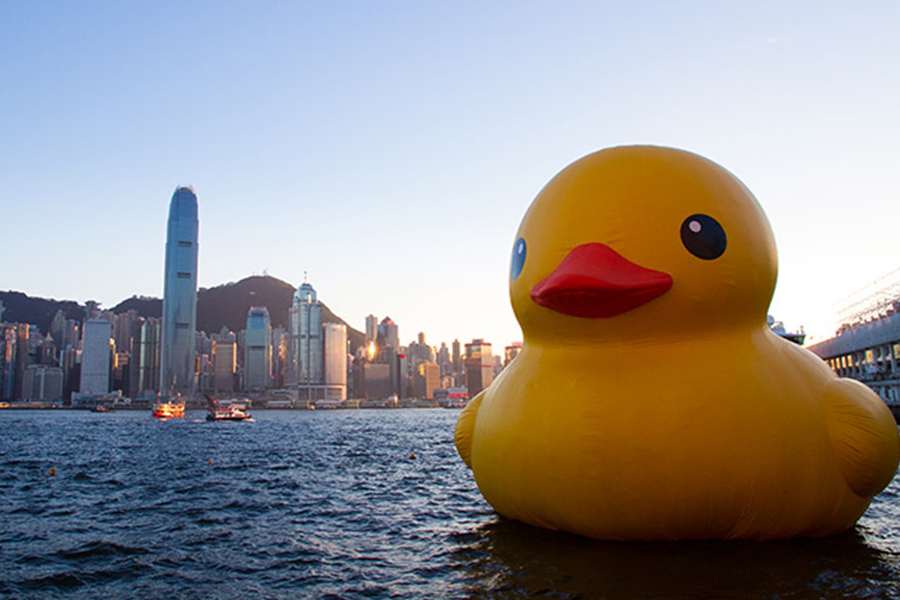

Cultural change has also been driven by Hong Kong’s sophisticated and highly receptive consumers, creating a unique and powerful relationship between art and retail. Hong Kong’s sophisticated retail sector has whole-heartedly adopted art as part of its arsenal of tools in keeping Hong Kong’s consumers supplied with new experiences and spectacles. Cultural events held in shopping malls such as K11, described by its owners as “the world’s first art mall”, art exhibitions in the IFC Atrium, Elements and Pacific Place, collaborations between luxury brand Louis Vuitton and Takashi Murakami have all made their impact on Hong Kong’s cultural landscape. At the time of writing, audiences both in Hong Kong and elsewhere remain captivated by Florentijn Hofman’s controversial but absurdly endearing giant inflatable yellow duck docked outside Harbour City, one of Hong Kong’s biggest malls, fulfilling the artist’s ambitious hopes for the work to become the catalyst for connecting people to public art.

The Hong Kong’s sophisticated retail sector has whole-heartedly adopted art as part of its arsenal of tools in keeping Hong Kong’s consumers supplied with new experiences and spectacles.

Being Creative

As these changes in the Hong Kong cultural landscape evolve, artists in Hong Kong are making work that is closely linked to the history and physicality of their surroundings, but which address issues that are human and globally relevant.

Discussing his work alongside artist Sara Wong and Aric Chen, Curator of Architecture and Design for M+ at Le Salon at Art Basel Hong Kong[4], artist Adrian Wong explained that his practice began with an interest in the gaps in Hong Kong’s history “I became really fixated on looking for traces of things that have entered the collective consciousness that have not been solidified within the history of the city”. One example is Wong’s Umbrellahead: I Will Find You (2010), a curious 30 minute theatrical production based on the life of Hollywood silent movie starlet Lei Mei who lived in the Western District, recalled through interviews with residents of the area who knew her or knew of her by reputation. Referencing Hong Kong’s many histories and the power of collective memory, it was not until research had made significant progress that the artist discovered that Lei Mei had never existed and that the character had been fabricated as a morality tale in the 1950s, yet her existence had attained the status of fact.

Adrian Wong is one of a generation of artists connecting Hong Kong history and mythology to larger themes of the human condition, such as in Wun Dun art bar open during the 2013 Art Basel in Hong Kong.

Wong’s practice has since explored Hong Kong’s physical gaps, spaces that have been erased, closed floors in buildings, missing elevator numbers and haunted places that have been buried from view. His recent project Wun Dun (2013) for the Absolut Art Bureau at Art Basel Hong Kong, described as an “art bar installation”, is a pastiche of a Hong Kong bar complete with fish tanks, utilitarian formica booths, fantastical animatronic musicians and surly waiting staff serving oolong tea vodka cocktails. At the same time, he subsequently discovered that the space had previously been closed to the public for decades on account of its inauspicious past use as morgue during the Second World War. “I think that the intersection of these deletions and these spaces within the psychology and history of Hong Kong and the perfect marriage of the deletions and redactions of the physical landscape of Hong Kong have made it a really fascinating place to conduct my “research””.

In Sara Wong’s performance video work Local Orientation (1998), the artist located the Para/Site art space on a map from which she extended four straight lines which she then attempted to trace on foot, traversing public spaces, negotiating physical obstacles and access to and through private spaces and semi-private spaces. Time and time again, following her mapped route across the city, Wong was struck by the prolific use of street railings and barricades, used ostensibly to protect pedestrians from roadside traffic, but, at the same time hastening the disappearance of Hong Kong street life. “Our street life is disappearing… Street activities are being taken out of the urban fabric of Hong Kong which is something that minimizes the diversity of the city as well.”

Street activities are being taken out of the urban fabric of Hong Kong which is something that minimises the diversity of the city as well.

Present and Future

The increased support for art and creativity and exposure to global art communities are beginning to make changes in the city. If Hong Kong’s creativity index were to be measured now in 2013, it would undoubtedly reflect the sea change in attitudes towards art in Hong Kong that have taken place in recent years.

The recent changes in the cultural landscape are markers of growing support for and receptiveness towards creativity, not only at an institutional and commercial level but also amongst the public at large and signify the transition of Hong Kong into a more creative society. Embracing and adapting to the challenges of the 21st century, Hong Kong creativity reflects the growing confidence and assertiveness of Hong Kong society towards its own identity. Looking forward, art from Hong Kong will take its place on the world stage once it captures the creative imagination of a global public, provoking and bringing that public closer to art.•

— Davina Lee is a curator, writer and lawyer – as well as being the founder and director of Diorama Projects. The objective of Diorama Projects is to identify, develop and realize projects that will stimulate artistic and cultural exchange and collaboration.

1 Home Affairs Bureau, A Study on Creativity Index, November 2005, accessed 2 June 2013, http://www.uis.unesco.org/culture/Documents/Hui.pdf

2 International Intelligence on Culture and Cultural Capital Ltd., Hong Kong Arts & Cultural Indicators – Final Report October 2005, accessed 2 June 2013 http://www.hkadc.org.hk/rs/ File/info_centre/reports/200510_hkartnculture_report.pdf

3 ibid. 17

4 Le Salon, Marc + Chantal Design, Swire Installation, Art Basel Hong Kong, 25 May 2013